Serakhs – Mashhad 190km

Mashad – Shiraz – Train

Shiraz – muddy field – 32km

Muddy Field – another muddy field 44km

Muddy field – Ardakan 71km

Ardakan – Yasuj 50km

Yasuj – Pataveh 50km

Pataveh – Kalvari 46km

Kalvari – River by the road 49km

River – near Burugen 40km

Burugen – Zibashar 70km

Zibashar – Esfahan 50km

Esfahan – Sagzi 52km

Sagzi – Abandoned Village 60km

Abandoned Village – Mahabad 73km

Mahabad – Kashan 92km

Kashan – Maranjab Desert Caravanserai 68km

Maranjab – Aran Va Bidgol 48km

Aran Va Bidgol – Tehran 30km + Bus

Total km ridden: 6643km

Our first month in Iran has flown by. The first week was spent cycling to Mashhad where we had a beautiful Warm Showers experience with Vahid and his family. In this the second most holy city for Muslims, we spent Christmas and awaited the arrival of Het’s best friend from Australia and her partner, Perry. For the next month we cycled from Shiraz to Tehran as a merry, treadly four.

Thoroughly spent from our five-day slog through Turkmenistan we vegged out in the Doosti (friendship) Hotel in Serakhs. We had now entered the Middle East and the stocks available in small town shops had greatly improved. Whilst Central Asia is famous for many things, food is not one of them. Canned horse meat and Russian candy was replaced with shelves stocked with halva, tahini, dates and pistachios. We were in heaven.

This new region was also marked by the steep change in female dress codes. Iran is an Islamic Republic, and so with that comes Sharia law and strict Islamic dress codes. For women this means wearing hijab, directly translated as ‘veil.’ Some interpret this as a loose scarf worn half way back on the head, with hair showing as is popular in the metropolitan areas of large cities like Tehran and Esfahan. In Eastern Iran, where we started our journey, most women in public wear a chador; a body length piece of (normally) black cloth that leaves only the face uncovered. So the streetscape looked vastly different, and Het soon got accustomed to wearing hijab under her helmet.

En route home from a shop in town, a car pulled along side and the lady in the passenger seat enquired as to where we were going. We soon invited Azam for tea at the hotel where she invited us to teach a class (or three) at her English language institute that evening. Therein ensued a hilarious evening of laughing children and laughing teachers, a la Tim and Het pretending to know how to teach English. We retired to Azam’s home and had a huge feast of Persian rice cooked with sliced potatoes on the bottom of the pan that crisp up, roast chicken, stewed greens and lamb and labneh. Our first day in Iran and we’d already been welcomed into a family’s home, confirming all the rumours we’d heard about Iranian hospitality.

This hospitality extended not only from individuals, but also from officials and organisations. As the sun set on our second evening a police car pulled us over near the town of Mazdavan. The two officers first asked Tim to remind Het that she needed to wear her hijab. Customarily in Iran if a man and a woman are together, the man is addressed almost exclusively, especially in the small villages. The two police officers then insisted they come with us into town to find us a place to stay. They settled for the fire station, and we whiled away an evening drinking tea and being entertained by the firemen.

The next day we battled some of the worst headwinds we’ve ever encountered. So forceful were they that we were in our low climbing gears and being thrown onto the gravel shoulder by the gusts from passing trucks. We decided that rather than reaching Mashhad that day, it would be prudent to bed down and wait for the next day to continue. We were lucky to come across a Red Crescent office as we decided this, and spent a warm, enjoyable evening with them. The Red Crescent is the Iranian equivalent of the Red Cross but also runs a remote ambulance and emergency service throughout the country. They have been an ongoing presence in our time in Iran…

In Mashhad we spent a splendid week with Vahid Arfa in the warm embrace of his family. Here we awaited the arrival of Georgia and Perry, our treadly three and treadly four. Vahid embodied all the wonder that is Warm Showers. His beautiful mother Taher cooked us the most delectable feasts every evening, shared on the finely woven Persian carpets sitting cross-legged around the table cloth. Through Vahid we gained an invaluable insight into the complexities of Iranian culture and politics and explored his beautiful city.

We began to learn of the discord between the government and its citizens which is so palpable and yet so hidden on the outside. Iranians are by in large dismayed at their international reputation and they rightfully blame the government for this tarnished image. People were keen to dispel this image by extending untold generosity and hospitality, which is also imbedded in their ancient culture. We read in a guide book that ‘Iran is more or less split between those who support the existing system – often rural people and the urban poor – as against those wanting change’ and we certainly feel this to be true. The locals we interacted with tended to navigate toward the anti-government contingent, our perceptions no doubt skewed by the fact that hard-line believers in the current Islamic regime are perhaps a little less likely to approach foreign infidels. This topic really warrants an entire blog post (or thesis) so we’ll leave it there and get back to the road.

Georgia and Perry arrived in Mashhad the day after Christmas and we welcomed our two new team members! A last minute decision for them to come and join us made for a whirlwind reunion at the airport where public affections had to be contained to a minimum in this very religious city. Het and George spent the evening staring into each others’ eyes and talking at a thousand miles an hour as Vahid graciously welcomed the new members into his home.

Mashhad is the second most holy city for Muslims after Mecca as it is the burial place of Imam Reza, the most popular Imam in Iran and the Shia Muslim world. A huge holy shrine sits around Imam Reza’s tomb, and as one might imagine, Mashhadi people tend to be some of the most devout Muslims in Iran.

The four of us visited the holy shrine the next day with Vahid and Taher, who had lent Georgia and Het two black chadors to disguise them as Muslims. Non-muslims are often not allowed into the inner sanctum of the shrine and are given conspicuous white chadors to alert the volunteers to their presence. The shrine is architecturally, mind-blowing. The whole interior of the labyrinthine rooms leading to the shrine are adorned with tiny pieces of geometrical mirrors reflecting the lights coming from stained glass windows and the crimson carpets. The exterior is a marvel of mosaic tiles covering the immense domes, archways and courtyards of the complex. At the heart of the shrine sits Imam Reza’s tomb, a huge structure enclosed in a silver cage. Men and women (separated by a large dividing wall) crowd into the burial chamber where the tomb sits, crying and wailing as they push forward to place their hands on the silver cage, all mourning an Imam that died 1200 years ago. For us as athiests, this display of such raw emotion based on religious beliefs was striking, and we emerged from the burial chamber speechless at what we had witnessed.

The next couple of days were spent preparing for the road again, replacing chains and cassettes for Tim and Het’s 6000km milestone and reconstructing Georgia and Perry’s bikes. Vahid bade us farewell with the promise to come and visit us in Tehran, and he waved from the platform as we boarded the sleeper train with four bikes and 14 panniers en route for Shiraz!

We arrived in Shiraz on New Years Eve and spent the evening celebrating with 30 of our host’s family, who all came from a village to the north of Shiraz. Eisa and Nooshie (friends of Vahid’s) lent Georgia and Het local dresses from the village, which were a great hit at the party. The first day of the new year, a Friday, was spent at a small farm block out of the city with Isa’s relatives having a huge picnic of kebabs, freshly made bread cooked in a stone tandoor and more chai than you could ever wish for. Friday is the only “weekend” day for Iranians, and it is often spent doing things like this, almost always with family.

We woke the next day excited at the prospect of our first day on the road as treadly four! The day, however, was somewhat short lived. With four of us to account four, things were a little slower. Day one, Tim left his sunglasses behind, Het directed us to the wrong road out of Shiraz so we had to take a more circuitous (and uphill!) route North and Perry and Georgia were enjoying the thrills of “which pannier is my [insert name of bike tool or item of clothing] in???” that all cycle tourists enjoy for their initial moments on the bike. We made it a mere 32km down the road and with the winter sun hours cruelly short, we pitched our tents in a muddy field in the dark. We assured George and Pez that things were usually not this bad and that it could only get better from here!

Whilst the temperatures plummeted during the night to – 10 degrees, the days were warm and the sun reflected off the snowy hills that we rode through for the next month. Things were on the up – countless cars pulled over offering us fruit, directions, “anything we could possibly need?” and on day two, a 2kg box of dates. On the morning of day three, we were shown by a man wandering down the dirt road we’d taken to find a camp spot, how to keep ourselves warm at night. He proceeded to light a bush on fire, miraculously with no starter, kindling or petrol.

We passed through Ardakan, a lofty mountain village high in the Zagroz mountains north of Shiraz, and the snow thickened on the side of the road. At roughly 2300m and with a meter of snow in all would-be campsites we opted to sleep in a small road-side shisha bar and teahouse.

The next day the road crested over a 2600m pass that offered spectacular views of the snow covered peaks and barren desert scapes. The rewards of the cold riding were reaped as we enjoyed a 40km downhill and some beautiful wild camping in the valleys beneath. With four of us to gather sticks it made the effort to reward ratio of a campfire in fairly deserted surrounds very favorable.

After six days of riding we had a very well timed rest day about 50km north of Yasuj. We were looking for a campsite about an hour before dusk and a kind man waved to us to come and drink chai with him in his farm stock warehouse by the side of the road. One of his friends who sipped tea with us whisked us back to his home and insisted we stay as long as we liked. He didn’t speak any English but his son, Mr. Mohsen, spoke an enthusiastically loud broken English that was, after being somewhat disconcerted at first as to whether he was angry or happy, delightful to listen to.

We woke the next morning to heavy rain and were invited to spend the day in Mr. Mohsen’s luxuriously warm living room as it bucketed down outside. In the evening we played card games with the family and cousins after a huge feast. Playing cards in Iran is illegal, as it is associated with gambling and general debauchery. In Mashhad we saw street peddlers selling packs of cards surreptitiously as though they were illicit substances.

Out into the cold the next day with considerable reluctance, we pushed on. We were riding on a major road now as we neared the next big city of Esfahan and the road was busy with lots of loud trucks that delighted in saying hello with numerous horn blasts. We managed to find a quiet little camp spot by a creek where we found a huge pile of fruit tree prunings waiting for us. George and Het set to making a cracking fire, but after almost an hour of fanning pathetic flames and inhaling carcinogenic amounts of smoke they admitted defeat and let Tim take over. Soon, a small fire was crackling away cheerfully. Georgia, in a merry state, made tea for the party and sat one mug on a stone next to the fire, intending for it to keep warm until Parry was finished setting the tent. Unfortunately, as George stepped away she knocked a stick out from under the mug and sent the contents all over the small fire, promptly extinguishing it with a steamy hiss. Tim succinctly dismissed himself and Het and George stifled giggles. The fire eventually got lit and all was well.

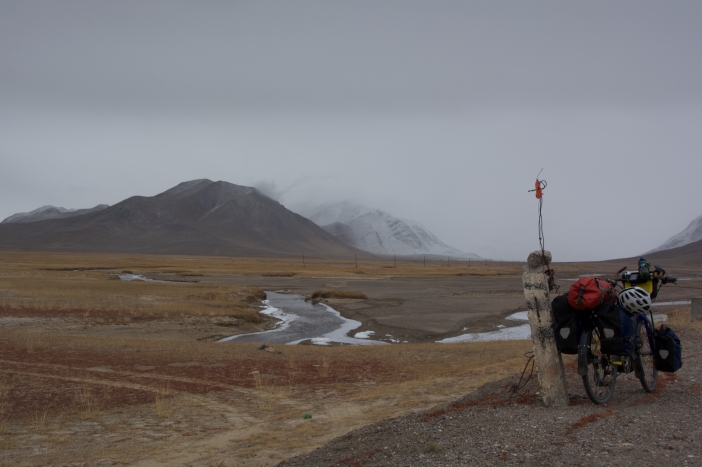

The next evening was also not without drama. After a long day of climbing we pulled into a conveniently located Red Crescent to ask if we could sleep the night. The volunteers manning the station looked enthusiastic, and called their boss to enquire. He flatly declined so we sheepishly headed back out in to the cold, bleak 2000m high plateau. The rain had caused the ground next to the road to form a thick clay-like mud layer that caked to everything that it came into contact with. We struggled down a small sidetrack, pushing the bikes once the wheels had clogged with mud, and found a spot to bed down for the night. Or so we thought.

A curious man had stopped by just before we began cooking dinner and seemed generally alarmed at our situation, “it’s cold, there’s wolves, you don’t know what it’s like here” was the general gist of his uncomfortably close interactions with Tim and Perry. After a few minutes of placating his concern, he hopped on his bike and went home for the evening. Or so we thought.

He had actually called the police, who promptly arrived on scene with five officers and lights flashing. Therein pursued a battle where we desparately tried to stay where we were, to not have to endure the inconvenience of breaking camp in – 5 temperatures and riding to another place in the dark. Several phone calls were made to dear Vahid in Mashad to translate the whole situation back and forth. Eventually they left the scene and we were sure we’d triumphed. Again, we were proved wrong several moments later when back up returned. Two police cars, two ambulances from the nearby Red Crescent and the head of the police for the region made it quite clear that we would be moving. We all packed into the ambulances (bikes and mud included) and said hello again to the volunteers at the Red Crescent. At 11pm, in quintessential Iranian fashion we all sat down for a welcoming tea by the head of the police, the head of both Red Crescents, police officers and volunteers, triumphant in their success of moving the idiotic foreigners to safe ground.

The final night of camping before reaching Esfahan was a delightful improvement on communication fronts. We pulled into a municipal park that had a tent sign on the entrance and set up. After a while, an equally concerned citizen, Gila, enquired as to our comfort levels, and we thought we would have to endure another night like the last one. However, Gila understood that the previous six months of such behavior had prepared us well for this life style and recognized the inconvenience of moving camp. Gila appeared the next morning with the mayor of the town, some members of the local fire brigade and onlookers with three bags of fruit, mountains of bread, cream, honey and cheese. They bade us farewell with a gift from the city of Zhibashar after showing us some interesting buildings in the town.

Esfahan was an array of cultural indulgence. A city adorned with perhaps the biggest number of ancient buildings, palaces, mosques, tombs and traditional houses of the wealthy families of bygone eras when the empire was at its strongest.

We had a lovely lunch with Madjid, a young man who worked in the perfume store beneath our hostel. He insisted we join him and his family in their home for some traditional Esfahani food, a tomato and lentil dish and the famous discs of candied sugar that accompany the requisite cups of tea. Gila came to visit us and we wandered the streets with her, her daughter Faisah and family. The evening ended in a men-versus-women laser tag competition where head-scarves were askew as all full-grown adults once again found their inner child and took it far too seriously.

With legs thoroughly rested after five days in the beautiful city we headed towards Tehran where Georgia and Perry would fly from in ten days’ time. Still with lots of time, we took a detour east of Esfahan to head towards the edge of the Dasht-e-Kavir desert. We decided to throw caution to the wind and turned off the major highway down a peaceful and well-sealed road that was unmarked on both our paper and GPS maps! What a good decision this was.

Glad to be out of the city and the awful Iranian traffic famed for its lack of rules and incredible congestion, we cycled through several picturesque tiny villages before setting up camp in the wide-open space. This stretch of road cuts through two large mountains in the distance, with Na’in to our east and Ardestan ahead. Several village ruins scattered the horizon, with crumbling mud brick walls and dead fruit trees the only traces of its former habitants. We spent a night in one such ruin, which made for one of the best camps of the month, the dead fruit trees made a huge fire and the walls sheltered us from the wind.

Two long days ride brought us to Kashan, the last town we’d ride to before hopping on a bus to Tehran. Riding into Kashan we faced strong head winds again, but now being treadly four made it a lot easier as we were able to share the load! The most notable thing about the road into Kashan is the huge pile of dirt forming a wall to the East of the highway; this is to hide what lies on the other side, perhaps the most controversial industry in Iran, the Natanz nuclear plant.

We camped in a park in Kashan to the bemusement of onlookers before heading out on a final jaunt into the Maranjab desert for three days. The 140km round trip was largely on a gravel and packed sand road that lead out to a huge salt lake and a centuries-old caravanserai that once welcomed travellers and traders along the old silk route. The ancient mud brick structure appeared on the horizon like some kind of mirage and we all postulated what it would have been like being atop camels 500 years ago. Camels in fact still live in this desert and we enjoyed their curious glances as we rode by. We spent an enjoyable rest day out in the desert, Tim and Perry practicing their mad skids as we rode out to see massive sand dunes and an ancient water well.

As treadly four we were gifted one last wonder of Iranian hospitality on our way back from the desert the next day. We had almost reached Kashan when we spotted another cyclist on the adjacent road heading in the opposite direction to us. He had some panniers on the back and we all waved manically at him. He came our way and soon extended the offer of chai, food, a place to sleep and bezam berim we were off to his house! Mahdi, our kind host, owned a carpet factory, was a keen cyclist and horse rider and was part of a cycle club in Aran Va Bidgol, just outside of Kashan.

An action packed first month Iran. In Tehran we farewelled George and Perry and welcomed Sarah and Richard, Hetty’s parents from Australia. They whisked us off for a whirlwind tour of Iran for two weeks before we headed North West to Turkey. More on that soon!